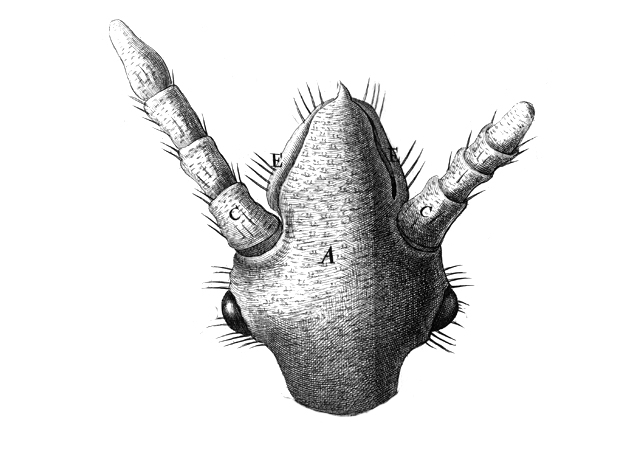

The following is extracted from ongoingness.space – a collection of writings on 'ongoingness', housed in a dissected version of Robert Hooke’s drawing of a louse from Micrographia (1665). Rather than being determined as a singular definition, ongoingness is elaborated as a quality: a continuous, generative way of operating. One that is nonlinear, transversing, networked, and a/multitemporal. The dispersed housing within the louse aimed to embody this approach.

The World Loanword Database (WOLD) provides vocabularies of 41 languages with comprehensive information about the loanword status of each word1. WOLD allows a consideration of the genealogical similarities between languages, as well as the historical moments in which certain languages diverged from one another. Loanwords, source words and donor languages can be found, along with the possibility of comparing loanwords across languages.2

WOLD is an evolution of a comparative linguistic practice that tends to culminate in lists that allow a quantification of the interconnectedness of the languages included: the Swadesh lists (1970s) are widely used lists of one hundred words chosen intuitively for their universality across languages. From an analysis of WOLD arose the Leipzig-Jakarta list (2009), which provided a one hundred word list of those words most resistant to ‘lexical borrowing’, a classification that applies to words that are adopted from one language to another without modification, transferring forms together with meanings. These words are the most stable, stubborn things, the least likely to be loaned out. What struck me was a recurrence in all these lists — none of the expected table-toppers, such as ‘I’ and ‘you’, but, sitting so comfortably, calm amongst the mess that has built up over the years — was that “Creature so officious, that ‘twill be known to every one at one time or other, so busie, and so impudent, that it will be intruding it self in every ones company, and so proud and aspiring withall, that it fears not to trample on the best, and affects nothing so much as a Crown”3 as Robert Hooke summarised in Micrographia in 1665:

Louse.

Louse places joint 15th on the Leipzig-Jakarta list: the body louse and the head louse each has a borrowed score of 0.05 – the lowest in the semantic field of Animals, alongside the nit and the fly.4

Louse is used as a means to contemplate ongoingness, throughout pluralist, multiplicitous, and multiversal lunges, where meaning, when you look for it, seems to slip away. I’m under no impression of louse as stable or singular in meaning that can be revealed; no notion of distinct essence on some unclickable underside. Though meanings may give a sense of themselves when things corrupt.5

In order to slip around this character — the louse-figure — it is worth delving into the standard definitions of the word, in all its noun and verb forms6, to develop a number of strands of linguistic looking that allow for mediations on the varying methods and trickery that constitute ongoingness (which operates across multiple times).7

The first: louse as creature, the wingless parasite. The close-up, the microscopic way in, a shell-like bulbousness – a route to be followed, as to “become animal is to participate in movement, to stake out the path of escape in all its positivity... to find a world of pure intensities where all forms come undone”.8 This kind of movement, the animal movement through pure intensity is one of speed, in which ongoingness is achieved through constantly being on the move, speed being “to be caught in a becoming that is not a development or an evolution”9 – that animal dragging.10

The second: louse as a contemptible or unpleasant person, one who we have all encountered, who weasels their way into things and then seems to stick in the mind for nights afterwards. Who touches surfaces and leaves grease marks – this will be our subsequent way of tracing them. This form of ongoingness can be on the haunted, personal level — a “tapping, tapping” 11, or a collective experience — a perceived continual threat to cultural stability, which constructs its own actuality: the lingering of racist/antisemitic beliefs.

Finally, the Americanism: to louse as to spoil or ruin something, which can come from the same altogether contemptible person – louse – or be partial, a one-off act of disruption. To louse in this sense, is a dynamic verb, one of action, rather than a stative one: a state of being that is best left with the contemptible louse, ideally alone, lousing. Dynamic incidents of lousing, then, are one-off revealed actions, which can be seen as distinct, as discrete lumpings of quanta. Keeping in mind that these re/appearances of disruption only allow us into the study of ongoingness at momentary points, but ultimately do not claim to pacify them, for “after the Empress had seen the shapes of these monstrous Creatures, she desir’d to know, Whether their Microscopes could hinder their biting, or at least shew some means how to avoid them? To which they answered, That such Arts were mechanical and below the study of Microscopial observations.”12

Arieh Frosh is an artist currently based in London where he is virtually completing a Master's degree in Contemporary Art Practice: Critical Practice at the Royal College of Art. He has previously been involved in Skin Deep magazine, and most recently 302_Redirect online festival.