The dirty woman is a hardwired gendered subject. Someone once told me they felt like a dirty woman after they slept with fifteen people in a week. Everyone is a woman's dirt. But I’m having trouble with categories. This is an essay about many people's lives and dirt. In Andrea Chu Long’s Females, she writes:

Everybody knows that men have much more respect for women who’re good at lapping up shit.

Shit, dirt, and waste all have their own fragmented ontology, and are not one particular entity but multiplicitous, many. Dirt dwells between peoples, places, thoughts, and behaviours. Contaminated, filthy, dissolved, murky, unkempt, words circulate the dirty subject and in their description categorise the dirty woman further. It’s an unclean, unclear matter, a matter of emotional disgust. Noticing how dirt makes us feel is a call to the affective, not an action or sequential thought.

The word dirty – di-rty – in part resembles the death of something – to di, to die. The pronunciation DIR-TEE, DIE-TY, DEITY, is many variations all within one word. D is the fourth letter of the English modern alphabet, pronounced [di] in the singular form and [de] in the plural. The etymology of die is a bit like to be dyed – a changing state, the ending of one, and the coming of another.

But who are we killing off? “Woman”, unlike “girl”, does not dwell in this abject, in-between state. To be a woman is to have lived through a temporality, to be thought of as fully formed. Unlike the adolescent, who is not yet, the woman has surpassed this in-between state. She says: I am a woman, I am older, I have the experience, life has dirtied me. Dirty, like the non-singular subject, is multiplicitous, many.

Singular subject: individual; one of a kind; unique; distinctive; separate

Multiplicitous subject: a state of being manifold; many; variety; plurality

The saddest part of the binary

When the curtain is lifted, the dirt is everywhere, symbolically our own. Several feminists might think the word dirty itself is problematic. The body is not-quite-one but also no-one. In the word no-one if you get rid of the latter ‘one’ you are given the word ‘no’ which, of course, is a refusal. To render one (no)self dirty is also a kind of refusal, a way of marking yourself and saying ‘hey I’m contaminated, you can’t touch me’. Most people don’t want to be associated with dirt. Or do they?

But that’s the problem – it isn’t just one person who is dirty, we are all dirty and perhaps the only differentiation is those who linguistically announce themselves to be just that, perhaps we want an alternative ordering to single out. The singularity of your dirt is not so special now because we all are each other and that is the plurality of dirt. Lots of films and books and letters and notes contain one dirty thing, even if it’s not obvious so it's not the dirt per se it's when we know and don’t know it's there. They eclipse one another.

Contamination offers a different delineation: noun.

- the action or state of making or being made impure by polluting or poisoning.

The American artist Kiki Smith’s work confronts issues of contamination, invisibility, poisoning, through the abject body, the body as many. In her work, the female body is always-already dirty, contaminated. Contamination is a bold entity to portray, not least because it cannot be centralised, but that dirt, as mentioned – origin is always-already unlocatable. For Smith, the manner of the dirty woman is captured in a momentary realisation, where natural order symbolises a combining of self and other, as an affective intertwinement. How much she saw herself in her work is unclear, yet many pieces present an uncanny relationship between the dirt of the self and another. The woman in Smith’s work is all but the same. It’s a method of narratology, storytelling.

Kiki Smith, Flowers in the Sky (2019) Lithograph / Serigraph / Collage on Japanese handmade paper, 68 x 98cm

But as much as narrative makes time orderly, its linearity also disallows for a queered sense of subject formation. In Flowers in the Sky (2019),dirt is two mutually interchangeable states. The penciled outline depicts a figure and the floorboard in which she sits. The figure, pensive sitting with their head turned backward cautiously invites the objects which flow their way. Stripped of any identification, and stark naked, the figure is defined by the flowing of ephemeral, the contamination of the flowers colour and substance upon their skin. The flowers are inspired by the death of Smith’s mother, the bouquet at the funeral, the corporal transfixed with the deceased. The meeting of flowers and natural ephemeral to the body serves as a double bind. It dirties the self whilst bearing witness to the diminishment of separates. To look at a body in its singularity is to witness it as a vulnerable subject awaiting change, where the tactility of skin is punctured. We feel it before we comprehend it as if the ephemera has a smell. It is a stream of consciousness that flows together and apart – to enact a weaving of similarities and separates; an intervention, an impression of dirtying, the di (death), of separate entities. In an interview from Phaidon Smith notes her artwork is about her changing relationship to ’transient natural forms with themes of life, death and resurrection’. Dirt had a peculiar relationship with death, the idea of catharsis and purification – does the removal of dirt change the cycle Smith notes?

Being contaminated with dirt, one might think of disease – a virus – an invisible entity which trickles through the body, uncontrollably. But dirt, so often is visible – the viscerality of it both seen and felt, known and acknowledged. In Flowers in the Sky we see the recognition of contamination – and although the flowers do not symbolise a stereotypical ‘dirt’ their placement nonetheless depict the succumbing of the self to an outside force. The dissonant expectations which force dirty women to maintain a subject-object enunciation disallow for contamination to be a positive force. Perhaps to be dirty, to participate in a dirty-ing, is to give oneself agency, to be a thing.

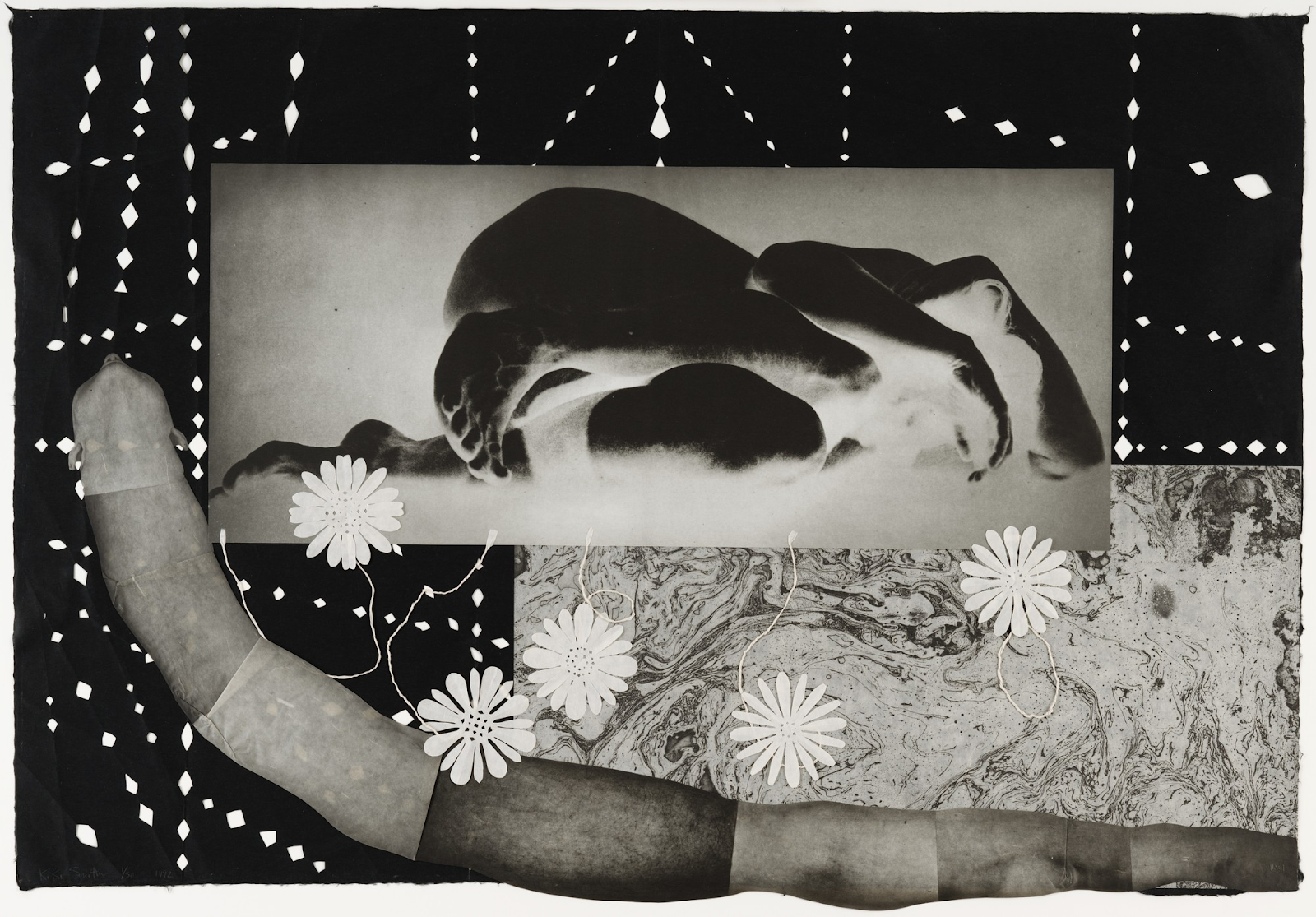

Kiki Smith, Worm (1992) Etching and collage on paper. Image: 1092 × 1570 mm

In another of Smith’s earlier works Worm (1992) the body is rendered as an intertwined form, surrounded by flowers, splurges and what appears to be a (phallic-esque) worm. The meeting of two entities are kept separate, a collage, yet the sensation of being consumed by another entity is an affective state. The human body and substance are not abject but instead permitted to dwell together. If dirtiness is an omnipresent, all-encompassing entity, one which meets us all, then the dirty woman is no different (if we’re to play the card of binaries). Dirt seems to have an overlooked relationship to multiplicity, to the many. What the worm viscerally demonstrates is that through movement, dirt meets the body, but also in a vulnerable, dirtied state we also might feel somewhat wormlike, other.

Quite compelling then, is the notion that Smith’s worm might not only reference transformation but the malleable parts of the self which can be consumed by other forces, entities. Laying in a foetal position, the figure is both relatable and unsettling, the worm bigger than the person itself. One does not feel the force of multiplicity nor singularity; both dually witness the other. The phallic object overtakes the (supposed) female figure – unsurprising

Yet even in Smith’s attempt to subvert the dirty woman, she remains to be so. The renewed aesthetic organisation of the work might not offer an alternative to such contamination, but the dirty woman is not an ‘I’ but a ‘we’, a point of opening; a reference point. To think of dirt as a ritualisation of catharsis, of dispelling that which contaminates us, is also to subject ourselves to a rejection of othering. Thus to rid oneself of the linguistic definition of ‘dirty woman’ is merely to own such a process instead of rejecting it. This notion of excess – of being too much – of bearing the weight of both physical and psychological dirt, begins to spill out, to expel. Dirt as something we both invite and do not evoke gives a sense of absoluteness. Smith’s images remind us often that dirt is something seen and not heard; portrayed and not felt. You don’t have to consent to be dirty or to be female, but you do have to acknowledge where such a definition might come from.

Purification, a word often associated with catharsis, has its own tangible quandary when placed within the realm of dirt, the dirty woman. If one was to undergo a removal of contamination, an eradicating of ‘dirtying’ then what would be left – or perhaps what in the first place were we removing? If the dirty woman is an acknowledgment of one’s societal place, then it is also a phrase which bodes well to eradicated. You don’t have to be dirty to be dirtied. To talk of the dirty woman is to participate in a gendered history, to linguistically signify that a woman’s dirt is not only her fault, but also her job.

The gendered subjectivity of “dirty” is universally applied; the naming of “dirt” is a societal application of worth. The dirty woman is ontologically unchosen, yet has power within its terminology. The dirty woman is all and but the same

Hatty Nestor is a cultural critic and writer, published in Frieze, The Times Literary Supplement, The White Review among many other publications. She is currently completing a PhD at Birkbeck, University of London.